Part One of this series can be found here.

In 2000, Will Ashon introduced me to Amaechi Uzoigwe, whose Ozone Management represented Mike Ladd, El-P, Antipop Consortium, Sonic Sum and Saul Williams. That summer, I flew to New York to carry out a two-week internship at the company.

Over the next few years, I made two more trips to intern for Amaechi. Ozone was defunct by the time of the next one, and Amaechi had co-founded an indie hip-hop label, Def Jux, with Company Flow’s El-P. I did a second two-week internship at the label immediately after 9/11, when the whole tone of the city had, understandably, transformed. Gone was the wildness and the revelry: New York was in mourning, with something more puritanical in the air. It was on this trip that I first met El-P, and was lucky enough to be present for the recording of one of the best moments on his solo debut, Fantastic Damage. I wrote about that experience in more detail here.

Then, in 2003, I went back for what was supposed to be six months. By then, the label had been forced to change its name to Definitive Jux, after Russell Simmons of Def Jam filed a lawsuit.

I made arrangements to live with Mike Ladd in the North Bronx, the relatively sedate, working-class neighbourhood a long way above the borough’s more notorious south. The light in the bathroom was broken, and there were roaches (Rob Sonic of Sonic Sum, who lived in the same building, blamed Mike for the presence of roaches in the building generally) and a virtually unused kitchen. Mike lived and worked in one room, sleeping on the couch and renting me the other. This spare room hadn’t been used for sleeping even before I arrived – it was mainly used for Mike’s epic war scenes.

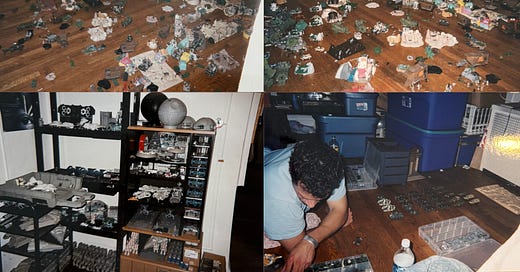

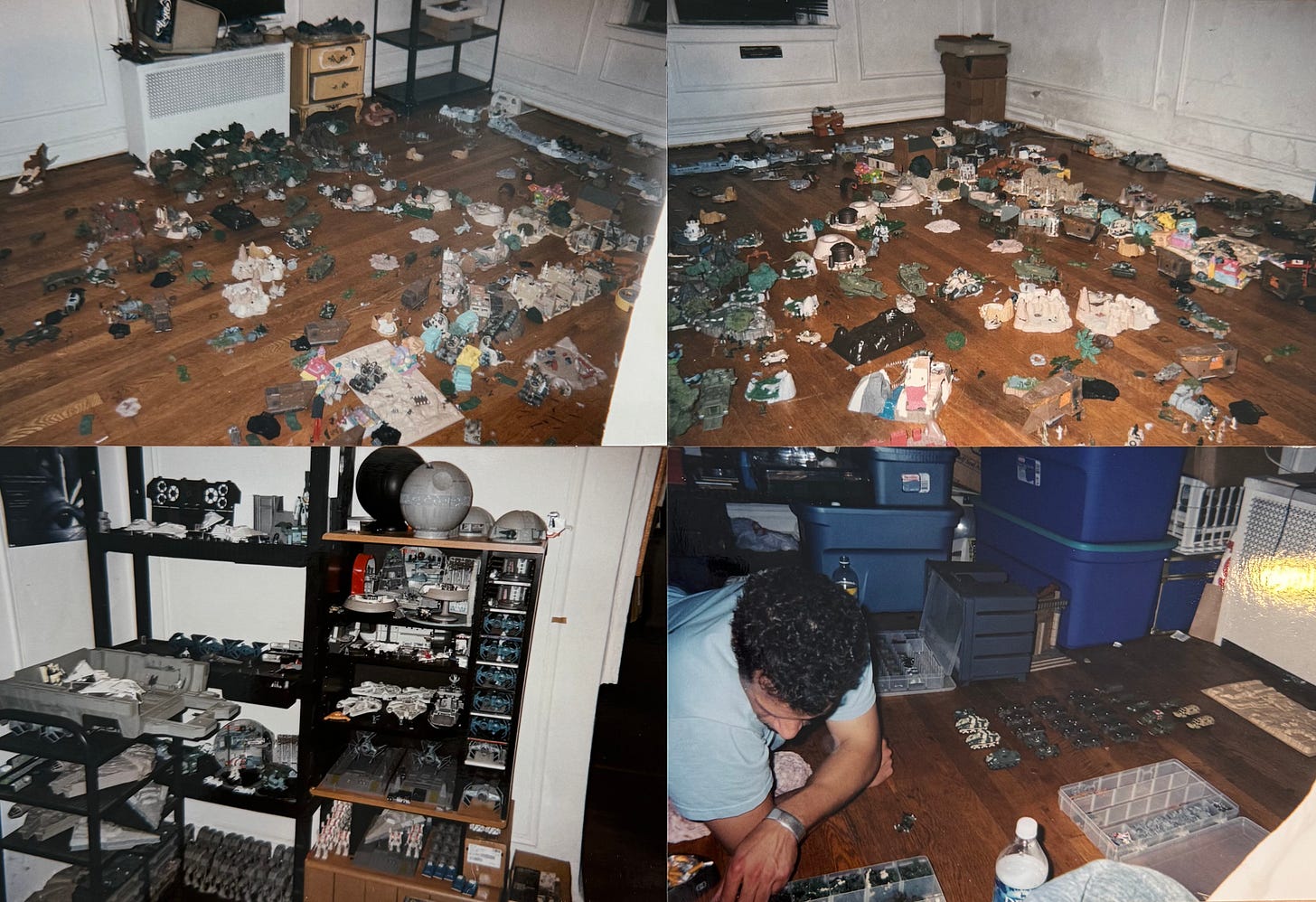

Mike had thousands of war toys – soldiers, tanks, helicopters, cannons and planes. They came from different brands and formats – there was Star Wars stuff among the toy soldiers and die cast military hardware1. They were arranged in vast formations across the floor; dozens of soldiers lined up on a platform, tank battalions with gunship support, forward operating bases and observation posts.

When I first saw them, I wasn’t sure whether to take the whole thing seriously. As Mike began detailing the epic narrative behind that spring’s war, the doubts began to fade.

‘Yo,’ he said, walking me around the apartment, where I stepped gingerly among the thousands of battle-ready soldiers. ‘So here’s the deal. These dudes’ – he gestured – ‘are monarchists who’ve lost control of their planet, so now they’re up in their ships, surrounding the place, waiting to take it back. These dudes are republican democrats, and they’ve got control, but they took heavy losses, and they can’t get reinforcements so they’re kinda in the shit.’

From here, things got detailed. ‘This guy here is a lieutenant, and he’s basically holding down this whole operating base because he’s brave as fuck. These guys failed to get him air support so he’s getting fucking creamed but he’s holding out. This guy here, on the other hand, is a total fucking pussy…’

On and on it went, a sci-fi war novel acted out by toy soldiers. In places, they lay on their backs, dead and defeated. And there were coins everywhere, dimes and pennies scattered among the bodies.

‘What are all these for?’ I asked.

‘Oh, those are the ammunition,’ Mike said, explaining how he flicked the coins at the soldiers to play out real battles, the result of which he had no foreknowledge of. ‘Pennies are cool, but dimes are perfect.’

Outside, the winter lingered late that April. I took the D or the 4 trains down to Lafayette Street and carried out the usual array of intern tasks at Definitive Jux’s office. But this time there was a problem: I’d fallen in love with a woman in London, and I was sick as a dog. The change in the city had made it less open. It was freezing cold and the streets were lined with dirty snow. I missed the woman terribly, and spent an inordinate amount of time in a north Bronx internet café, hoping she’d emailed me. She had gone traveling in Southeast Asia for six months, and wasn’t always able to do so. To make matters worse, I’d entered into an accidental and largely unsuccessful career as a male model.

Three months into my six months’ placement, I decided to cut my trip short and follow my girlfriend out to Thailand. I got drunk with a barman at my favourite restaurant in Alphabet City, talking about jazz. This seemed very sophisticated until I got back to Ladd’s apartment and realised I’d lost my passport, leading to a grim twenty-four hours of seeking an emergency one in a blinding snowstorm2.

I remember the sick feeling of dread in my gut as I said goodbye to Rob and Mike and took a cab to JFK. I’d dreamed of this – of being in NYC and working in hip-hop – for so long. And now I was throwing it away.

For the two months I was in Thailand, I was cut off from music news. At the end of the trip, the woman and I flew back to London together. She sat for most of the journey with a blanket over her head, digging her nails into my wrist and silently weeping in distress that her long-awaited travels were over. We were not destined to be together.

When we got back, I found a copy of Jockey Slut, the long defunct music magazine that was popular at the time. I flicked through the news and features until something caught my eye. There was an article on a new London rapper called Dizzee Rascal (aka Dylan Mills,) and there, in a separate inset, was a reaction to his album from Will Ashon of Big Dada Recordings.

‘Well,’ he said. ‘This is about as raw as it gets.’ He went on to praise Dizzee’s debut, Boy In Da Corner, in a tone that suggested he was a little astonished by it. I knew I had to get this record immediately. As I remember it, the Jockey Slut article referred to Dizzee having broken out of the garage scene. No one had yet come up with the term ‘grime.’

I took the Tube into central London and bought a vinyl copy of Boy In Da Corner from Selectadisc. The album didn’t disappoint. It was immediately clear that the promise that had lurked within UK Garage – that of a truly homegrown form of British rap music – had been fulfilled. The music had stripped garage down to raw, rude bass, lashing drums and ominous digital melody. Dizzee’s rapping was incredibly assured – his flow varied and rapid, playing with the edges of control when he got really animated. The lyrics were stark and brutal. In interviews, Dizzee said he didn’t want to make a ‘conscious’ record. This was the term used for more ethically minded hip-hop at the time, records that sought to push back on anything gangsta, to outline the problem but also the solution.

Dizzee wasn’t interested in that. As we’ll see, life could be brutal and violent for young black men and women in London in 2003. He wanted to tell it how it was, and if he didn’t exactly celebrate the life he depicted, he certainly wasn’t going to critique it. As a result, the music managed to capture the menace of the Bow, E3 streets that Dizzee was raised in, as well as the exhilarating, high-octane rush of being young.3

All of this was exemplified by the album’s key single, I Luv U. Over icy, menacing synths and metallic hi-hats, a woman’s chopped up voice says ‘I love you.’ And then the bass kicks in – rude and bouncing. In an interview, Dizzee’s then manager and producer, Cage, would say that in the studio Dizzee had ignored all the sophisticated sounds he’d tried to show him, and gone straight for the crudest ones. The drums are hard, and in a pattern that clearly springs from British black music, but feels entirely new. The minimalism is shocking and somehow slightly frightening. And in the lyrics, Dizzee draws a picture of uncaring sex, unwanted pregnancies and bad outcomes. The chorus has a synth melody that’s a little reminiscent of Afrika Bambaataa’s Planet Rock - but scarier.

These choruses have two parts. In the first, Dizzee and the female vocalist take turns to complain about being chased, respectively, by a bitch and a prick. In the second, they have a conversation, as if sitting on a wall or a tower block walkway.

‘Ain’t that your girl?’ the woman asks.

‘Na, I ain’t got no girl,’ Dizzee replies.

‘I swear that’s your girl.’

‘Course it ain’t my girl.’

‘She got juiced up.’

‘Oh well.’

‘She got jacked up.’

‘Oh well.’

The inventiveness of a teenager structuring a chorus like this, creating something that so vividly brings his subject to life, is astonishing.

I was completely blown away by Boy In Da Corner. I’d left NYC early, and part of me felt I’d failed in my pursuit of American hip-hop. Arriving home to discover British grime was perfect timing, as if maybe the decision hadn’t been so wrong after all.

To be continued…

One memorable evening, Mike gave me a croggy on his pushbike, all the way from the North Bronx to (I think) FAO Schwarz at Rockefeller Plaza, in order to look at a large toy tank which had just been released. He didn’t buy it.

The day after this sudden snowstorm in early April, 2003, Robert Atkins, the founder of the Atkins diet, slipped on an NYC sidewalk, dying a few days later from the resulting head injury.

In a description that made me wince even at the time, and now would be outright unacceptable despite its speaker’s good intentions (and absolute lack of racism), one of the then Ninja Tune staff who’d been a mentor to me described Boy In Da Corner thus: ‘You know that feeling when you turn onto a street in Hackney and there’s five black lads standing around, and you’re not quite sure what they’re going to do?’ he said. ‘That’s how this album sounds.’ The past is a foreign country.

Ah, Dizzee. One of my favs! Saw him in Brooklyn some years ago. Also a big fan of Amaechi.